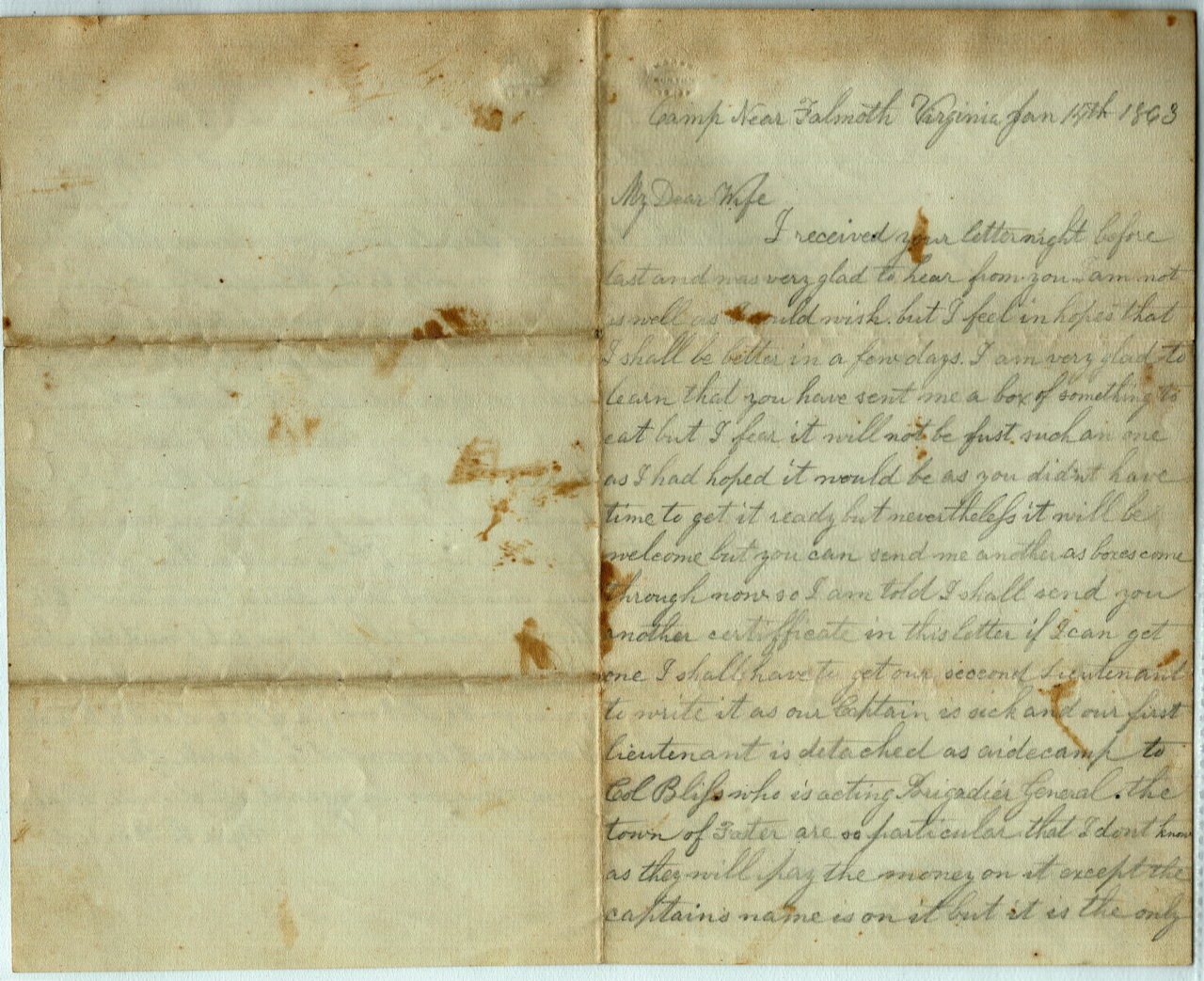

My Dear Wife,

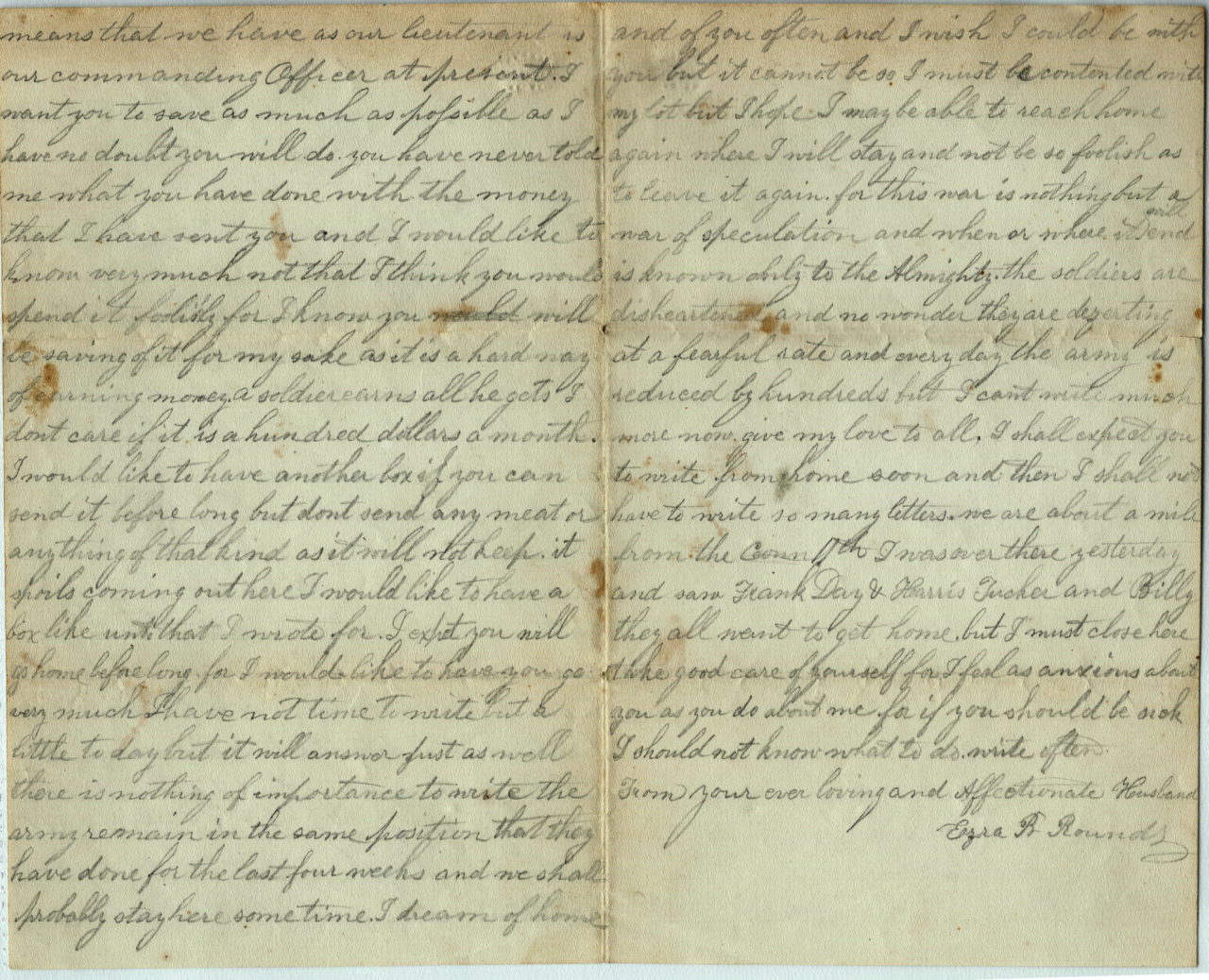

I received your letter night before last and was very glad to hear from you. I am not as well as I could wish but I feel in hopes that I shall be better in a few days. I am very glad to learn that you have sent me a box of something to eat but I fear it will not be just such a one as I had hoped it would be as you didn’t have time to get it ready but never the less it will be welcome, but you can send me another as boxes come through now, so I am told. I shall send you another certificate in this letter if I can get one. I shall have to get our Second Lieutenant to write it as our Captain is sick and our first Lieutenant is detached as aid de camp to Col Bliss¹ who is acting Brigadier General. The Town of Foster² are so particular that I don’t now as they will pay the money on it except the captains name is on it but it is the only means that we have as our lieutenant is our commanding officer at present. I want you to save as much as possible as I have no doubt you will do. You have never told me what you have done with the money that I have sent you and I would like to know very much. Not that I think you would spend it foolishly for I know you will be saving of it for my sake, as it is a hard way of earning money. A soldier earns all he gets. I don’t care if it is a hundred dollars a month. I would like to have another box if you can send it before long but don’t send any meat or anything of that kind, as it will not keep. It spoils coming out here. I would like to have a box like the one I wrote for. I expect you will go home before long for I would like to have you go very much. I have not time to write but a little today but it will answer just as well. There is nothing important to write. The army remains the same position that we have done for the last four weeks and we shall probably stay here sometime. I dream of home and of you often and wish I could be with you but it cannot be so I must be content with my lot but I hope I may be able to reach home where I will stay and not be so foolish as to leave it again for this war is nothing but a war of speculation and when or where it will end is known only to the Almighty. The soldiers are disheartened and no wonder they are deserting³at a fearful rate and every day the army is reduced by hundreds but I can’t write much more now. Give my love to all. I shall expect you to write from home soon and then I shall not have to write so many letters. We are about a mile from the Connecticut 11th.⁴ I was over there yesterday and saw Frank Day and Harris Tucker and Billy. They all want to get home. But I must close here. Take good care of yourself for I feel anxious about you as you do about me for if you should be sick I should not know what to do. Write often

Your loving and affectionate husband, Ezra B. Rounds

Footnotes

1- Col. Bliss – Zenas Randall Bliss, Arlington National Cemetery Website. He served in Texas until May 9, 1861, when he was captured with the command of Colonel I.V.D. Reeve, 8th U.S. Infantry, by a Confederate force under General Earl Van Dorn, and he was held as a prisoner-of-war, at San Antonio, Texas, and Richmond, Virginia, until he was exchanged on April 5, 1862. He was appointed Colonel, 10th Rhode Island Volunteers, August 1862; fought in the Fredericksburg campaign, December 1862; then in the Division of the Ohio in Kentucky to May 1863; transferred with the 2nd Division IX Corps, and with that organization took part in the siege and capture of Jackson, Mississippi.

2- the town of Foster – is 20 miles east of Providence RI

3- Desertion on both sides was a massive problem. Records show that in 1863, 85,000 officers and men deserted from the Army of the Potomac per www.thomaslegion.net.

Union Army

In view of the conditions, which prevailed in the war department and in the Union army, it is not surprising that desertion was a common fault. Even so the actual extent of it, as shown in the official reports, comes as a distinct shock. Though the determination of the fully number is a bit complicated, the total would seem to have been well over 200,000. From New York there were 44,913 deserters according to the records; from Pennsylvania, 24,050; from Ohio, 18,354. The daily hardships of war, deficiency in arms, forced marches (which sometimes made straggling a necessity for less vigorous men), thirst, suffocating heat, disease, delay in pay, solicitude for family, impatience at the monotony and futility of inactive service, and (though this was not the leading cause) panic on the eve of battle – these were some of the conditioning factors that produced desertion. Many men absented themselves merely through unfamiliarity with military discipline or through the feeling that they should be “restrained by no other legal requirements than those of the civil law governing a free people”; and such was the general attitude that desertion was often regarded “more as a refusal to ratify a contract than as the commission of a grave crime.”

The sense of war weariness, the lack of confidence in commanders, and the discouragement of defeat tended to lower the morale of the Union army and to increase desertion. General Hooker estimated in 1863 that 85,000 officers and men had deserted from the Army of the Potomac, while it was stated in December of 1862 that no less than 180,000 of the soldiers listed on the Union muster rolls were absent, with or without leave. Abuse of sick leave or of the furlough privilege was one of the chief means of desertion. Other methods were: slipping to the rear during a battle, inviting capture by the enemy (a method by which honorable service could be claimed), straggling, taking French leave when on picket duty, pretending to be engaged in repairing a telegraph line, et cetera. Some of the deserters went over to the enemy not as captives but as soldiers; others lived in a wild state on the frontier; some turned outlaw or went to Canada; some boldly appeared at home; in some cases deserter gangs, as in western Pennsylvania, formed bandit groups. To suppress desertion the extreme penalty of death was at times applied, especially after 1863; but this meant no more than the selection of a few men as public examples out of many thousands equally guilty. The commoner method was to make public appeals to deserters, promising pardon in case of voluntary return with dire threats to those who failed to return. That desertion did not prevent a man posing after the war as an honorable soldier is evident by a study of pension records. The laws required honorable discharge as a requisite for a pension; but in the case of those charged with desertion Congress passed numerous private and special acts “correcting” the military record.

4- Connecticut 11th – according to Wikipedia – was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment was attached to Williams’ Brigade, Burnside’s Expeditionary Corps, to April 1862. 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, Department of North Carolina, to July 1862. 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, IX Corps, Army of the Potomac, to April 1863. 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, VII Corps, Department of Virginia, to July 1863. 2nd Brigade, Getty’s Division, Portsmouth, Virginia, Department of Virginia and North Carolina, to October 1863.